I’ll be presenting at MariaDB Day 2026 in Brussels on HammerDB performance tuning and benchmarking methodology that delivers real-world architectural impact, How MariaDB Achieved 2.5× OLTP Throughput in Enterprise Server 11.8. This blog post provides some of the insights and background that went into this work.

In 2025 HammerDB began working with MariaDB engineering to analyse OLTP scalability on modern hardware platforms and to identify architectural bottlenecks that limit throughput at scale. The goal was not to tune a benchmark, but to use accurate, comparable and repeatable workloads to identify fundamental serialization points in the database engine. You can read the blog post here on the results of that work: Performance Engineered: MariaDB Enterprise Server 11.8 Accelerates OLTP Workloads by 2.5x

To deliver improvements as quickly as possible, these changes were introduced in MariaDB Enterprise Server 11.8.3-1, with updates further progressing into the community version from MariaDB 12.2.X onwards.

Note: It has been highlighted that some recent public benchmarks of MariaDB evaluated earlier MariaDB 11.8 Community builds that did not yet include these scalability improvements. To observe the latest performance engineering benefits you should use the latest version of MariaDB Enterprise Server 11.8.3-1 or above or MariaDB Community Server 12.2.1 (latest version at the time of publishing of this blog).”

1. Why Modern Hardware Changes Database Scaling

You may notice that the subtitle explicitly says MariaDB 11.8 delivers up to 2.5x higher OLTP throughput on Dell PowerEdge R7715 servers powered by AMD EPYC™ processors. Database performance can never be viewed in isolation from the hardware. If you have a familiarity with Moore’s Law you will know that CPU transistor density historically doubled approximately every two years, leading to faster, cheaper, and more efficient computing power. However, in the chiplet era, performance scaling is no longer driven purely by transistor density—system architecture, topology, and interconnect design now dominate real-world database scalability.

Amdahl’s Law, USL, and CPU Topology

The classic underlying scaling model applied by performance engineering is Amdahl’s Law, which states that overall speedup is limited by the serial fraction of a workload. Even small serial sections cap scalability as core counts rise. The Universal Scalability Law extends this by modelling contention and coherency overheads, explaining why performance can plateau or even regress at high concurrency.

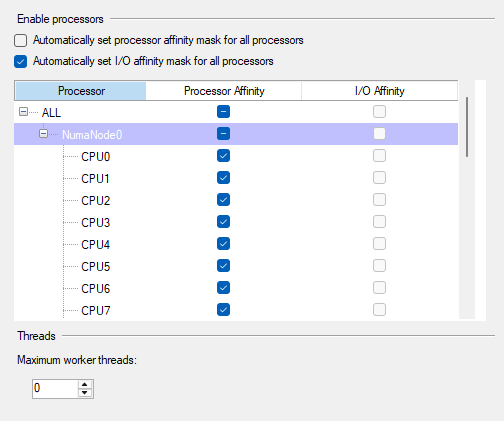

In the chiplet era, CPU topology adds another dimension: NUMA boundaries and interconnect latency now create intra-CPU scaling knees that classical models did not explicitly predict. Modern database performance engineering therefore requires topology-aware analysis, not just thread-level scaling curves. For this reason we partnered with StorageReview to access the very latest Dell system to evaluate MariaDB performance.

The server platform used was a Dell R7715 equipped with:

-

-

- AMD EPYC 9655P 1 x 96 cores / 192 threads

- 768 GB RAM (12 x 64GB)

- Dual PERC13 (Broadcom NVMe RAID)

- Ubuntu 24.04

-

Given the topology focus it is vital to cross-reference performance research on multiple systems. The results were also verified and additional testing conducted on systems based on the following CPUs:

-

-

- Intel Xeon Gold 5412U / 128GB RAM

- AMD EPYC 9454P 1 x 48 cores / 96 threads 256 GB RAM

-

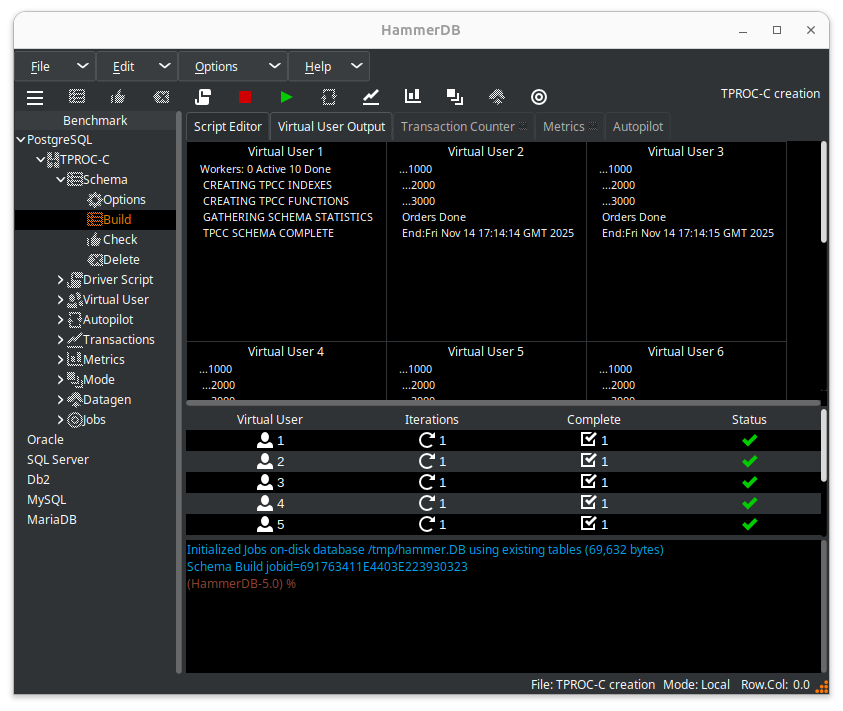

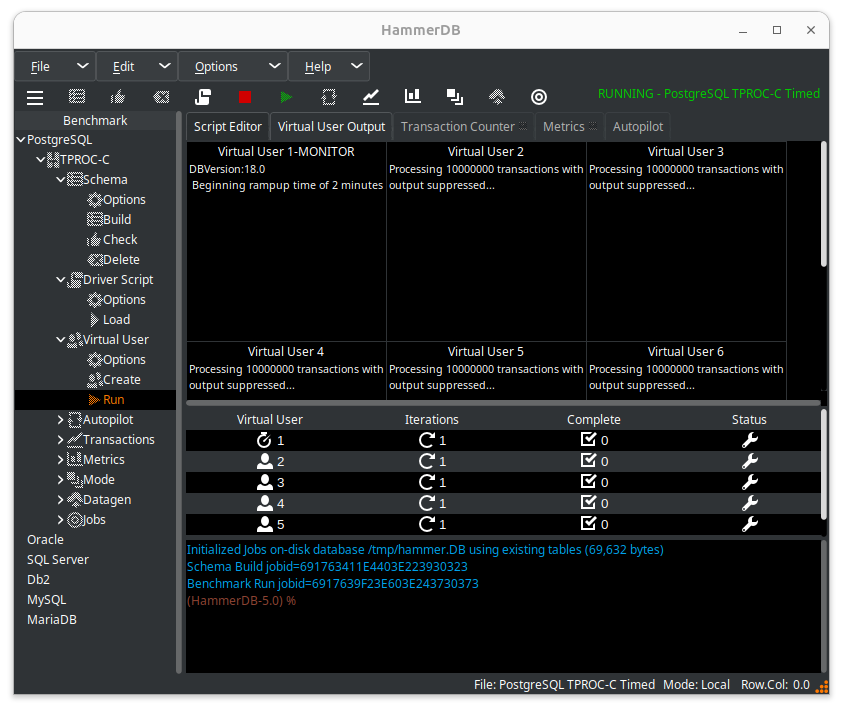

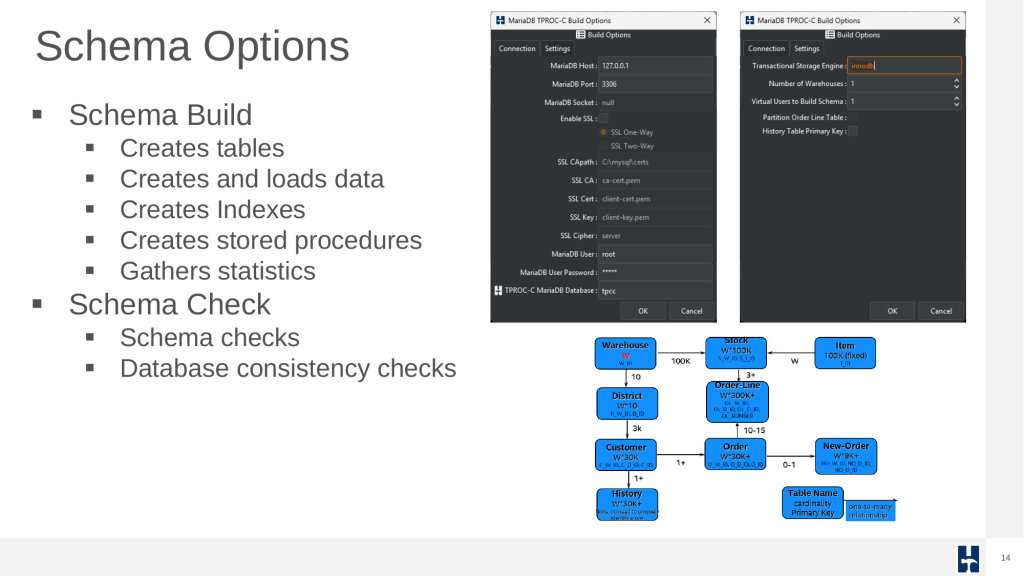

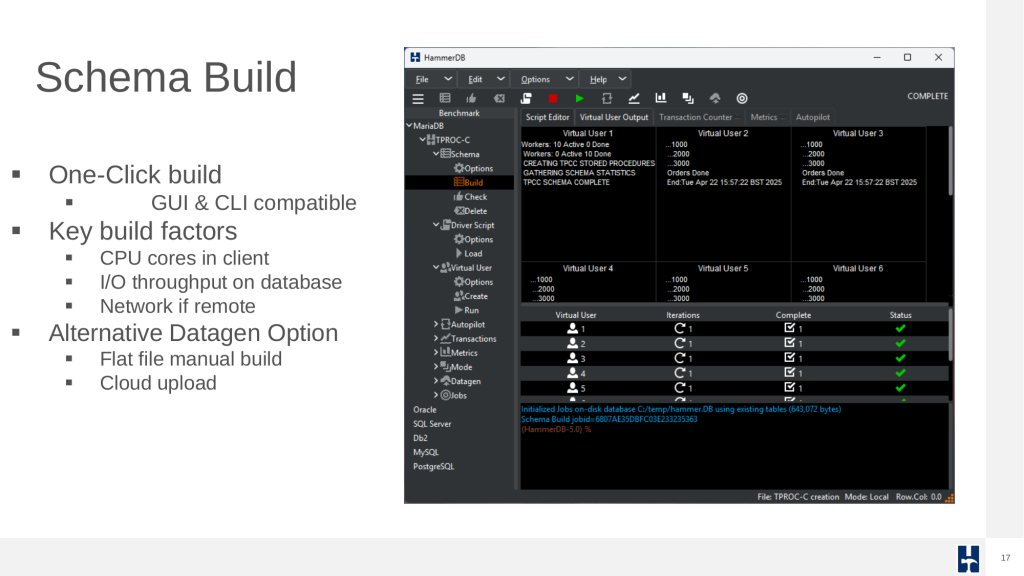

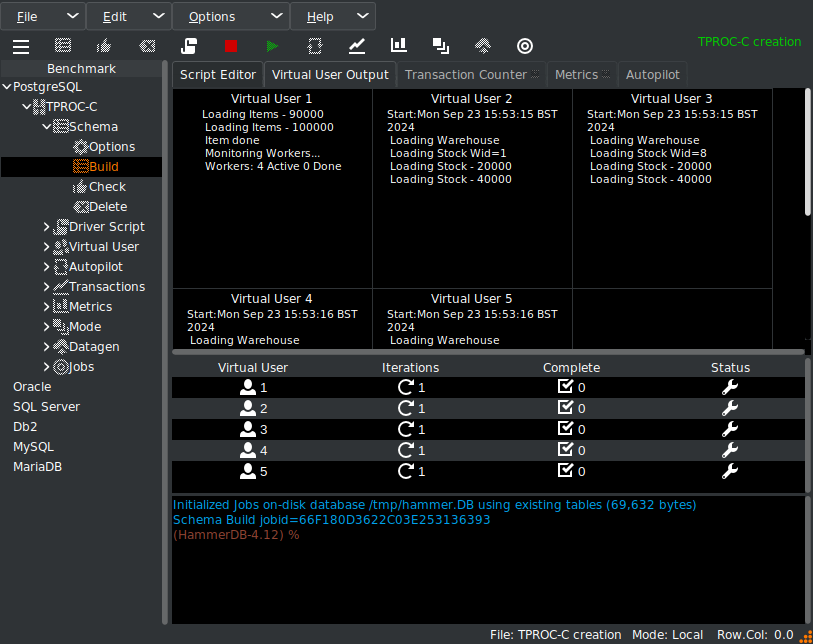

2. The HammerDB TPROC-C Workload

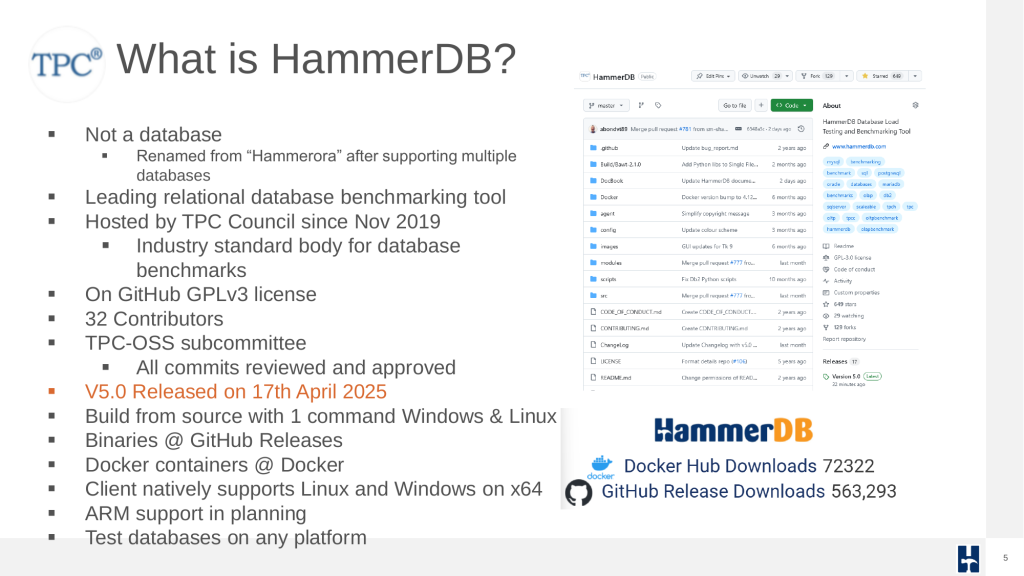

HammerDB and TPC

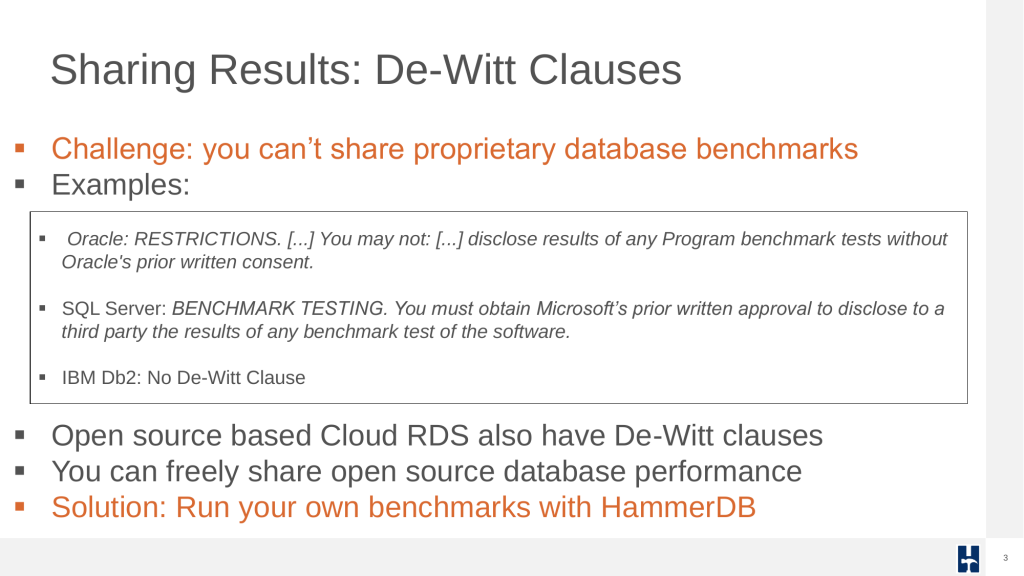

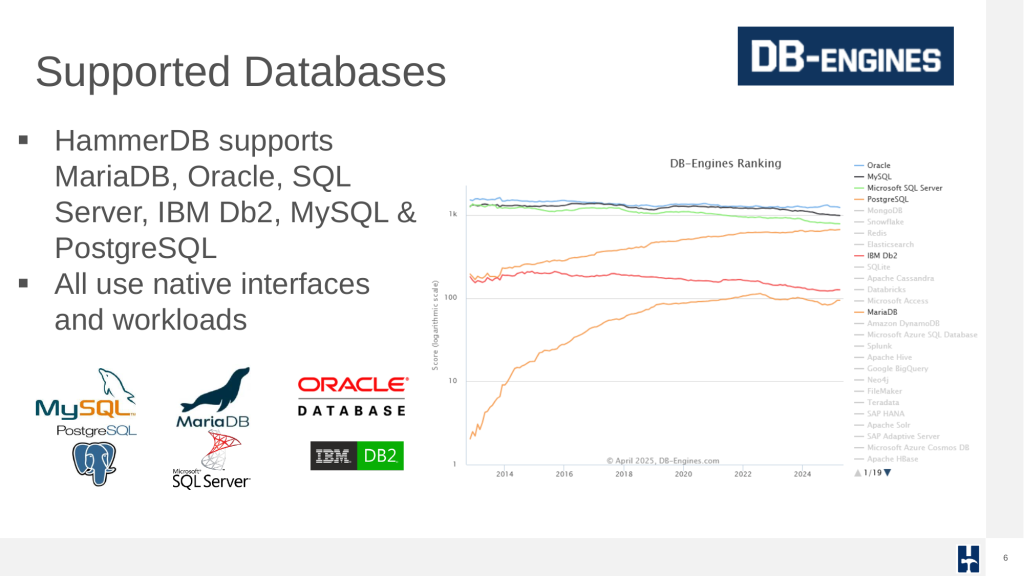

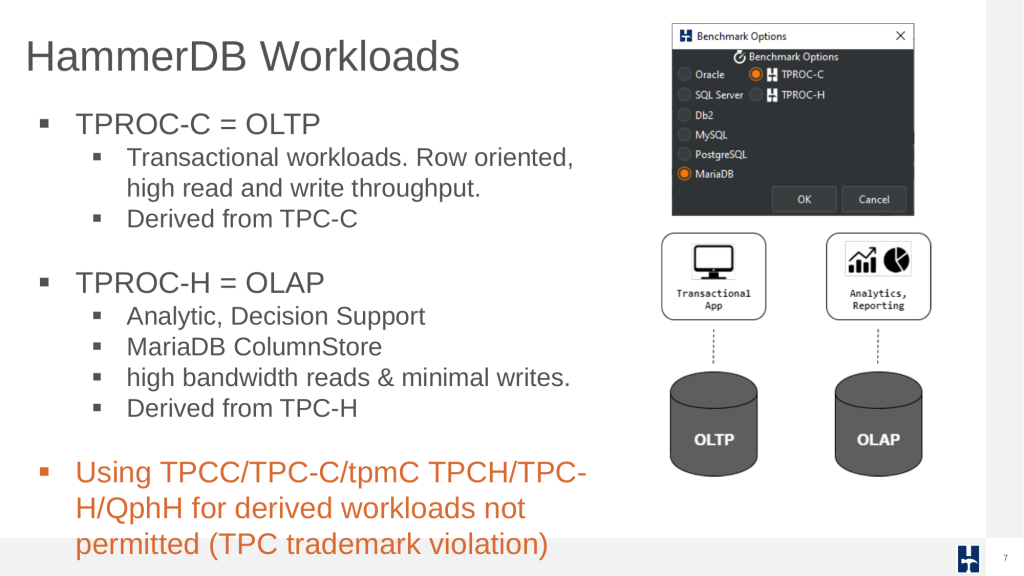

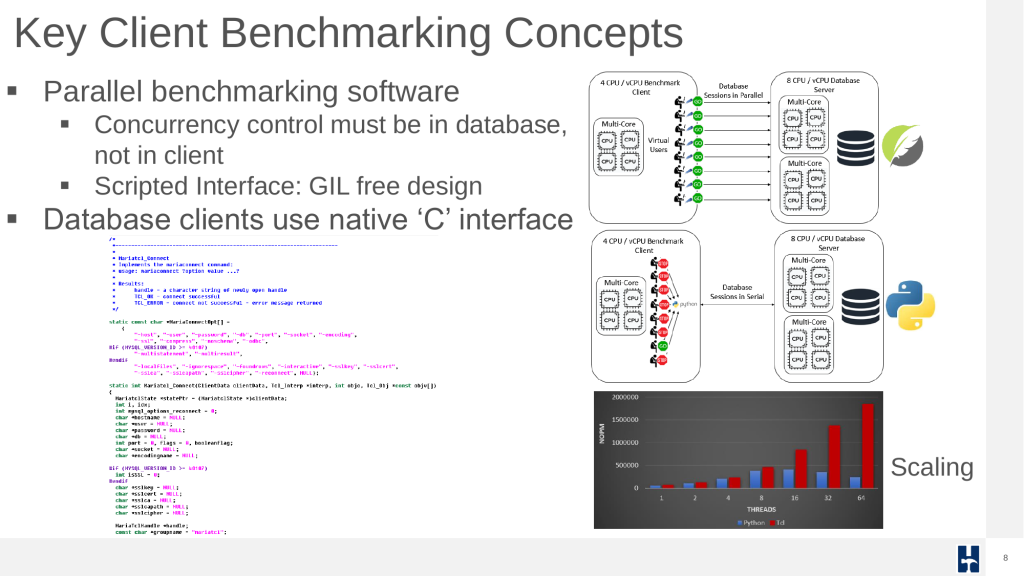

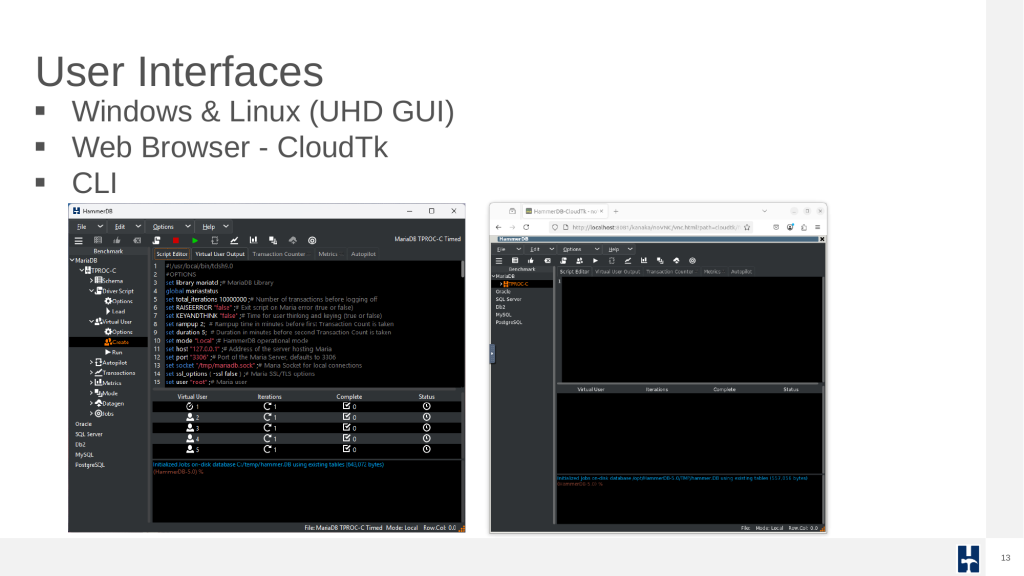

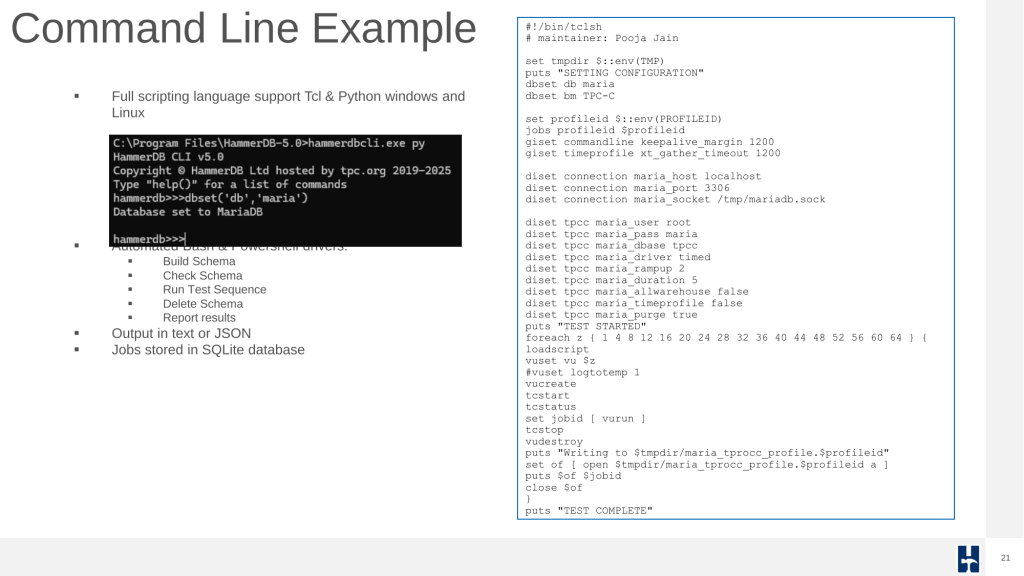

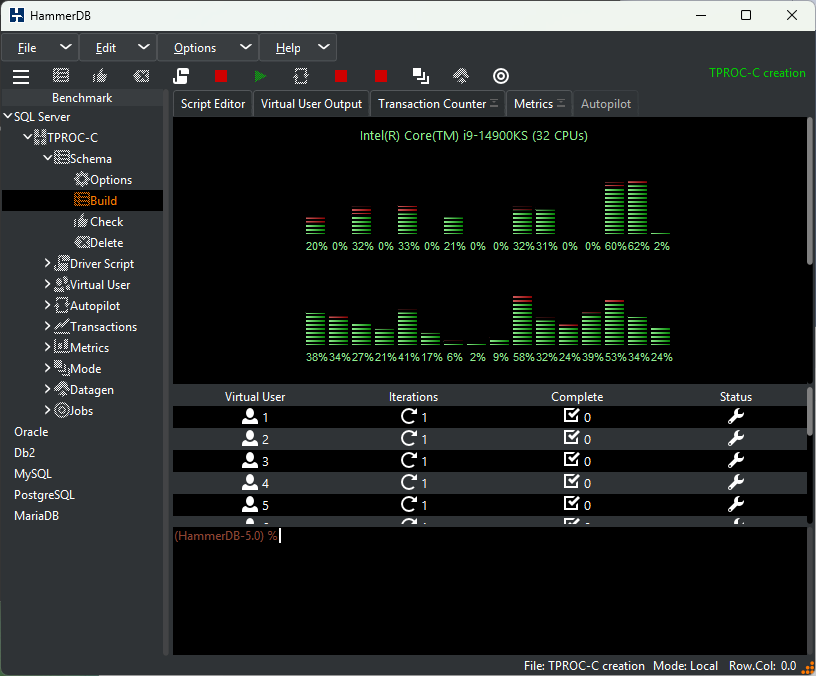

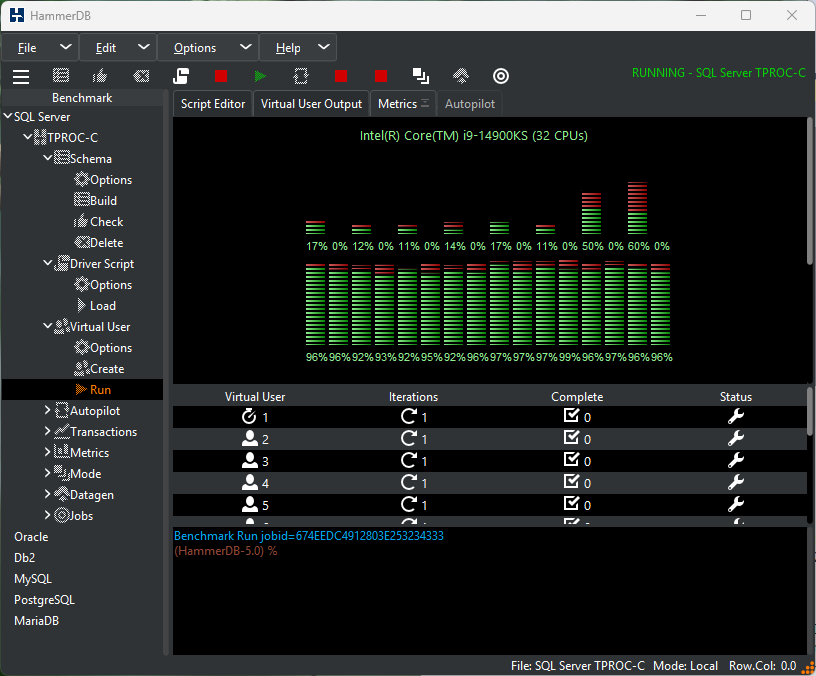

HammerDB implements the TPC-C workload model as an open-source, fair-use derivative called TPROC-C. It is designed from the ground up for parallel throughput and modern hardware scaling. In 2018 HammerDB was adopted by the TPC and is hosted by the TPC-Council with oversight via the TPC-OSS working group to ensure independence and fairness. HammerDB supports not only MariaDB, but Oracle, Microsoft SQL Server, IBM Db2, PostgreSQL and MySQL running natively on both Linux and Windows, enabling a wide range of workloads and insights. Anyone can contribute to HammerDB.

TPC-C trademark and naming

Although hosted by the TPC-Council, HammerDB does not use ‘TPC’ or ‘TPC-like’ terminology as defined by the TPC fair use policies. TPC-C is a trademarked benchmark requiring audit and configuration disclosure. Non-audited workloads should be labelled ‘TPC-C-derived’ and not use TPC-C or tpmC in its naming, hence the HammerDB TPROC-C workload. Using the trademark without audit and disclosure not only violates the TPC trademark but can mislead readers about comparability with published results.

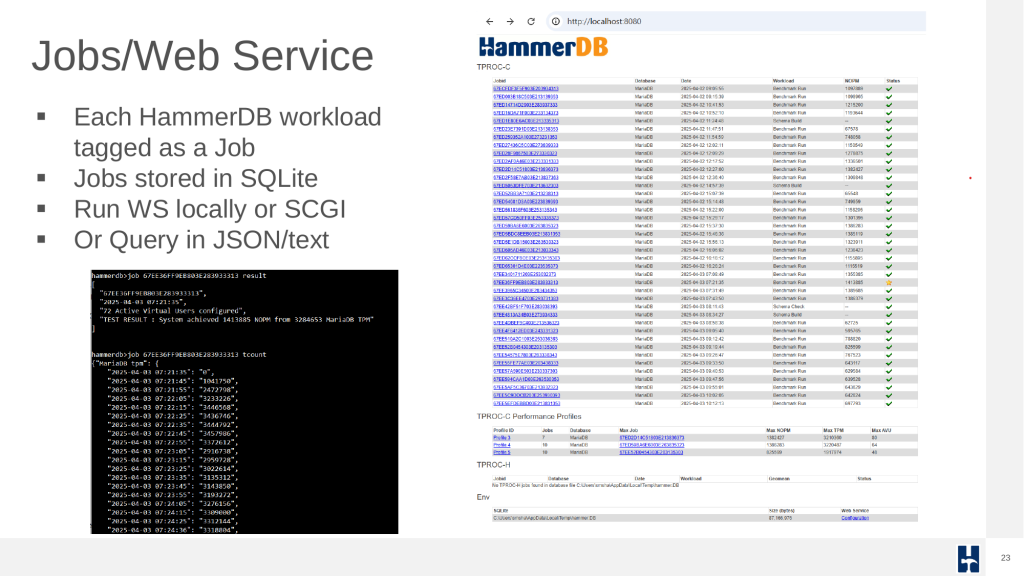

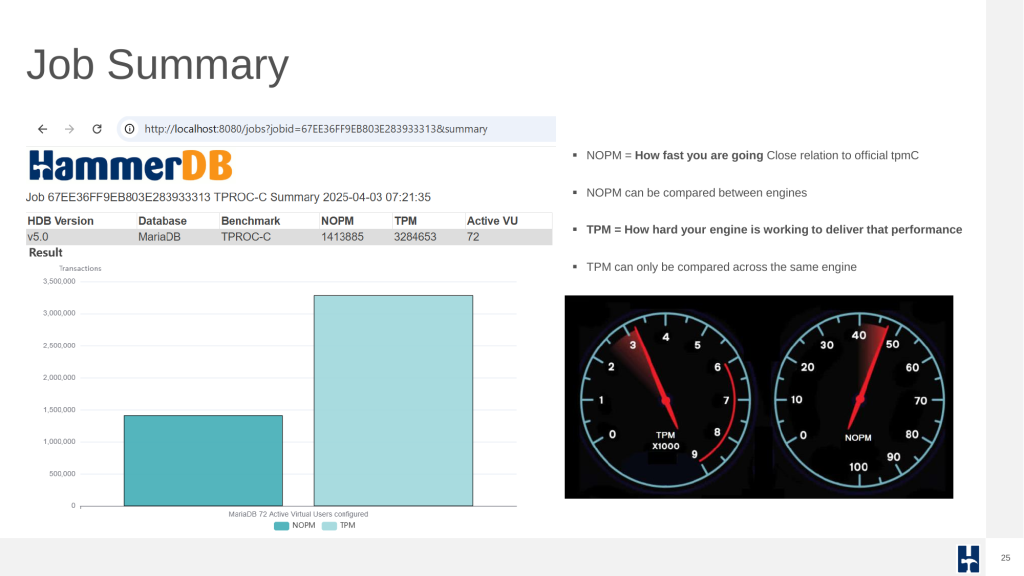

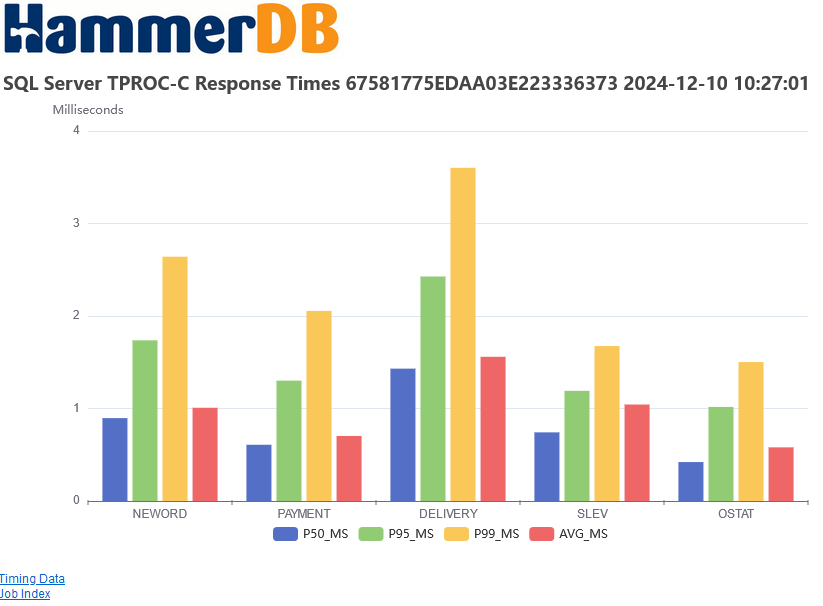

Transaction metric: tpmC and NOPM

TPC-C defines performance in committed New-Order transactions per minute (tpmC). HammerDB defines its own TPROC-C metric called NOPM which means (New Orders Per Minute). HammerDB also provides a database engine metric measurement called TPM (transaction per minute), however TPM cannot be directly compared between database systems. A system may execute more database transactions while completing fewer workload transactions. This also extends to low level database operations such as SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE statements. NOPM is the meaningful metric to measure TPC-C derived workloads.

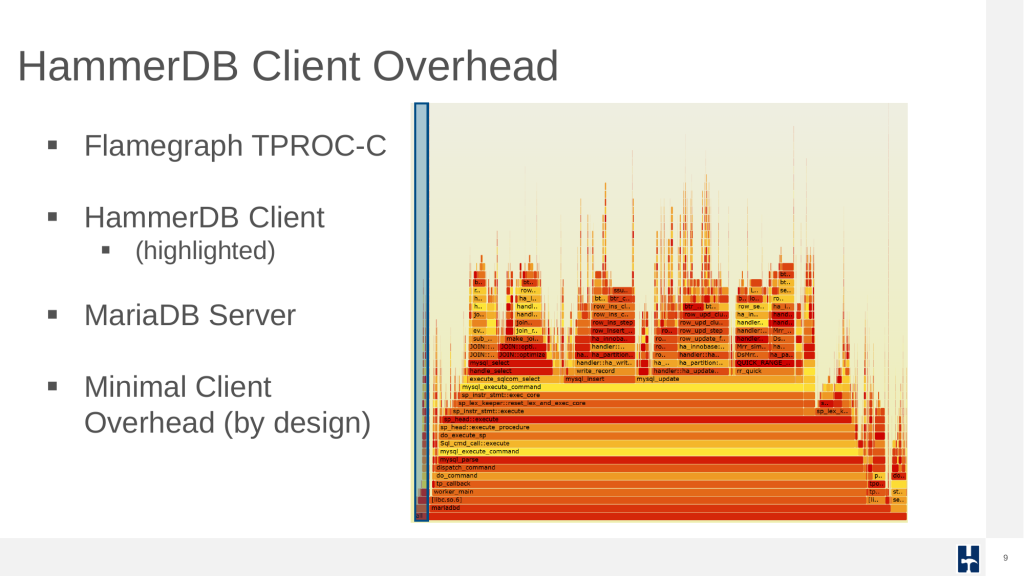

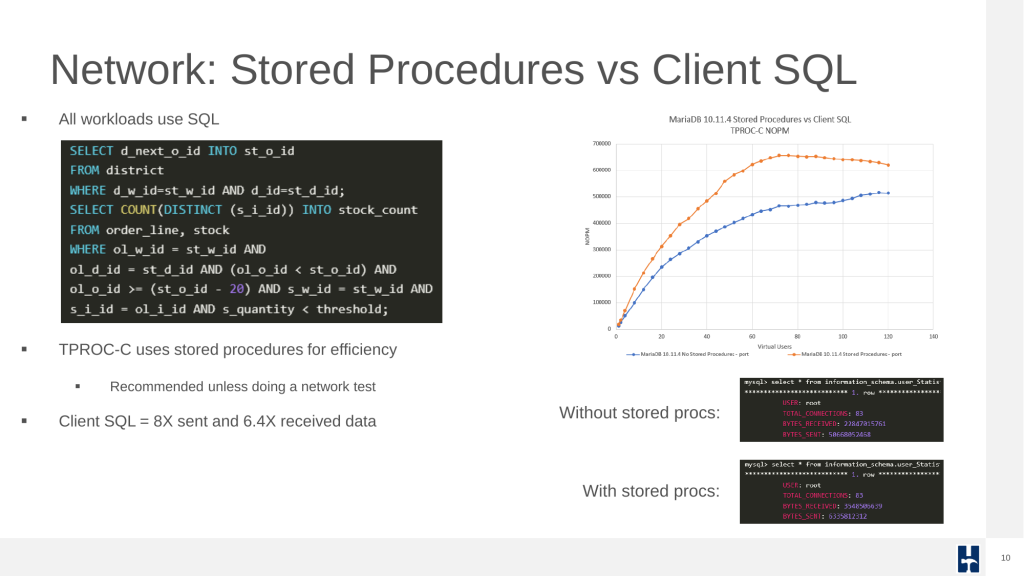

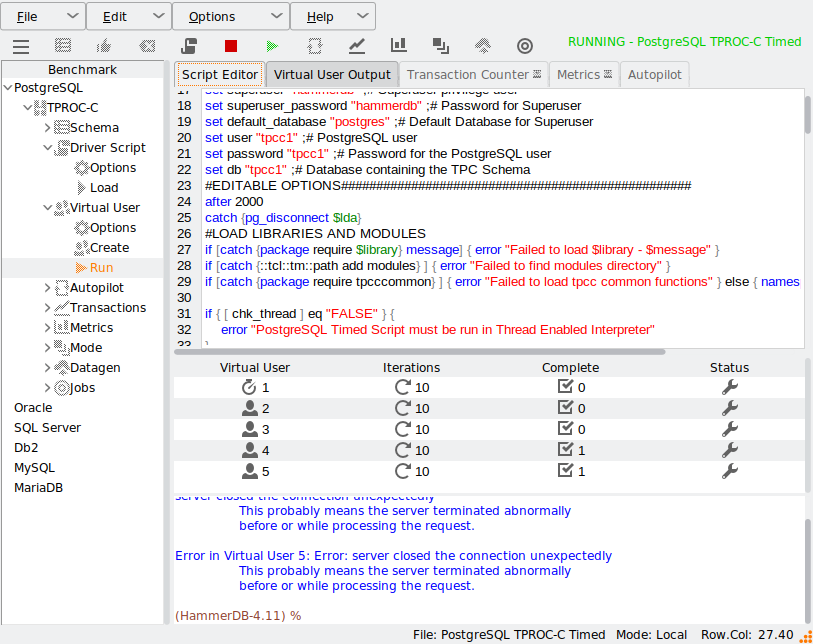

Stored procedures vs client SQL

HammerDB uses stored procedures to reduce network round trips and client-side overhead. Client-side SQL execution can increase network traffic by an order of magnitude and bias results of database engine scalability downward.

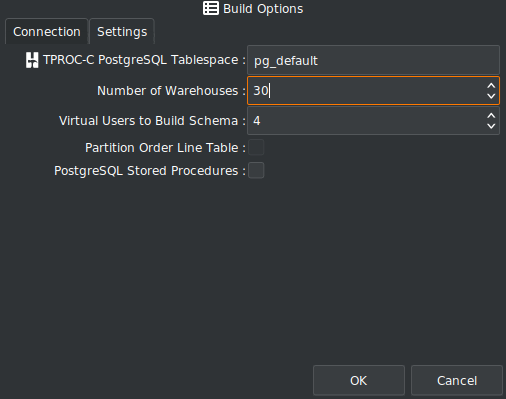

Sharded schemas vs single-instance scaling

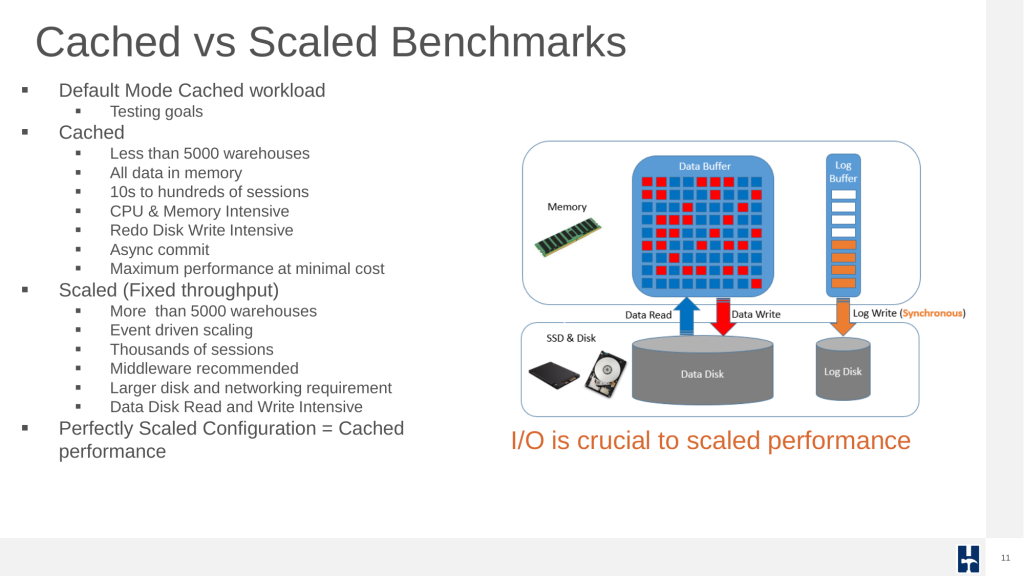

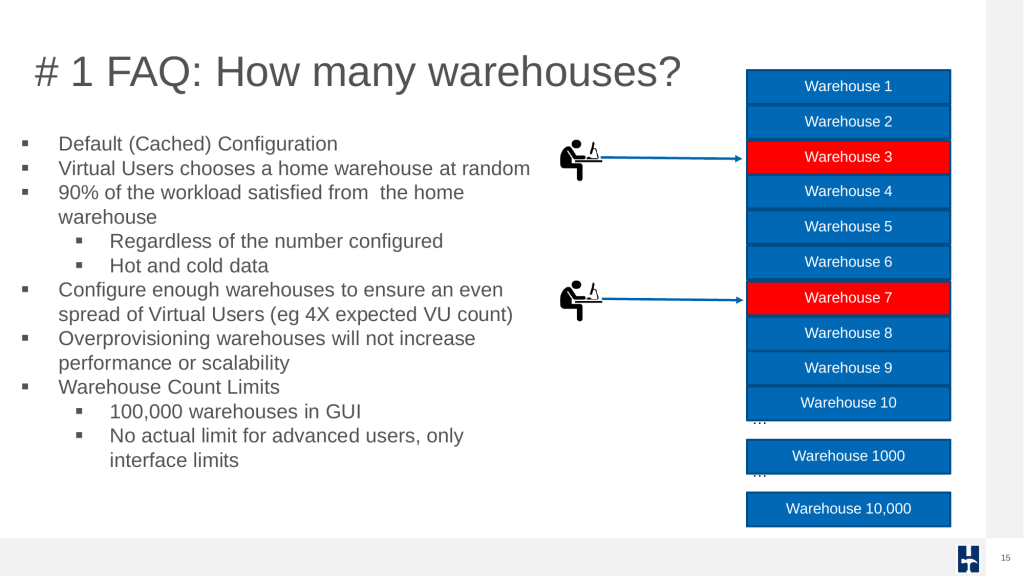

The TPC-C specification defines a single schema with N warehouses. Multiplying schema instances (for example, 10 schemas × 100 warehouses) removes contention and changes scaling behaviour, effectively benchmarking a sharded architecture rather than a single schema. HammerDB implements both cached and scaled derived versions of the TPC-C specification, both enable scaling to 1000’s of warehouses without the need for sharding.

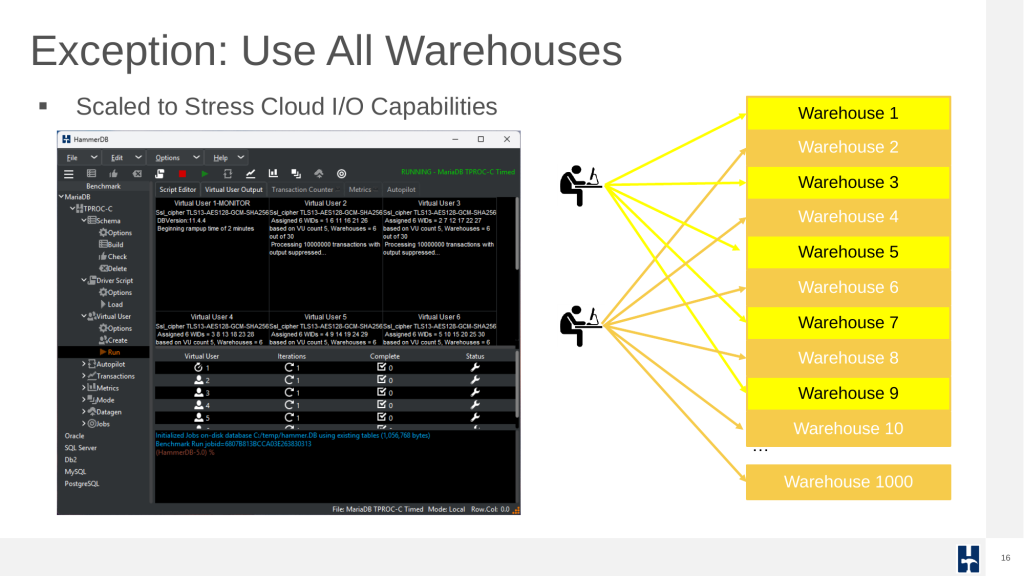

Warehouse access patterns and I/O bias

The cached implementation of HammerDB follows the default implementation concept of virtual users having a home warehouse. HammerDB also has an option called “use all warehouses” where random warehouse access patterns are intended to drive physical I/O and bias benchmarks toward storage rather than database concurrency control and buffer pool management. Cached workloads are typically used to observe core engine scalability.

With HammerDB we have a proven methodology known from years of observation to align system comparison ratios with official audited TPC-C results.

3. MariaDB 10.6 Baseline and Analysis

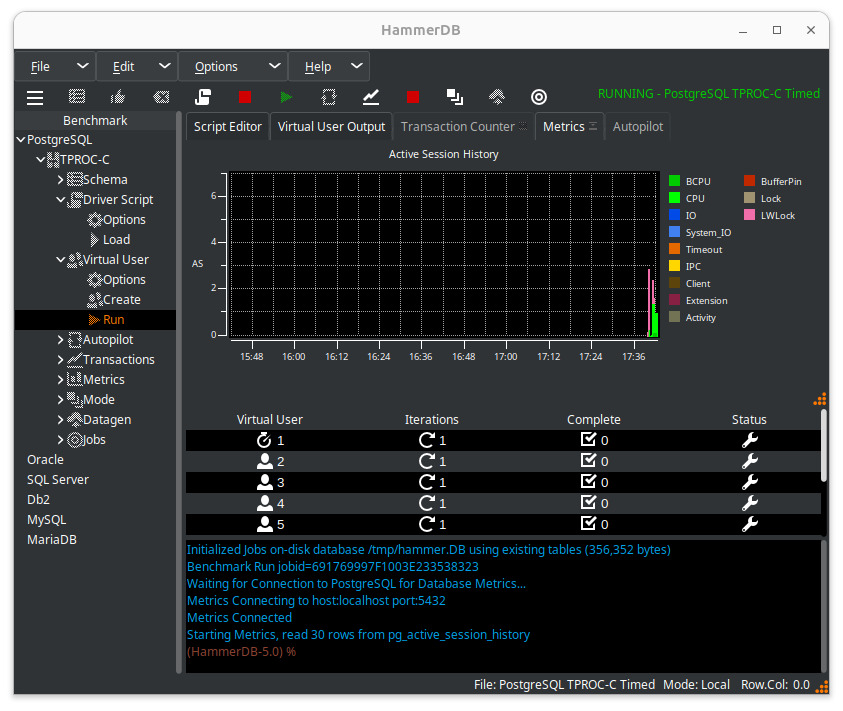

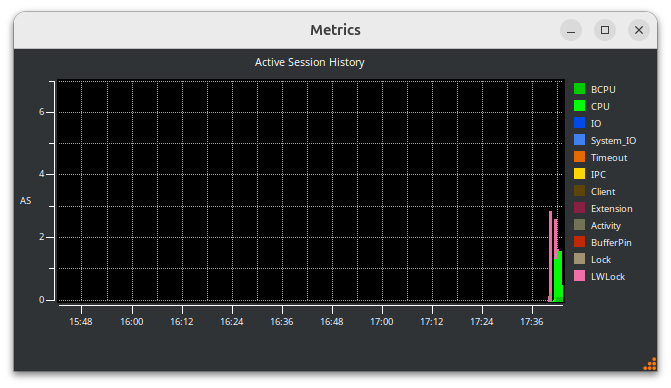

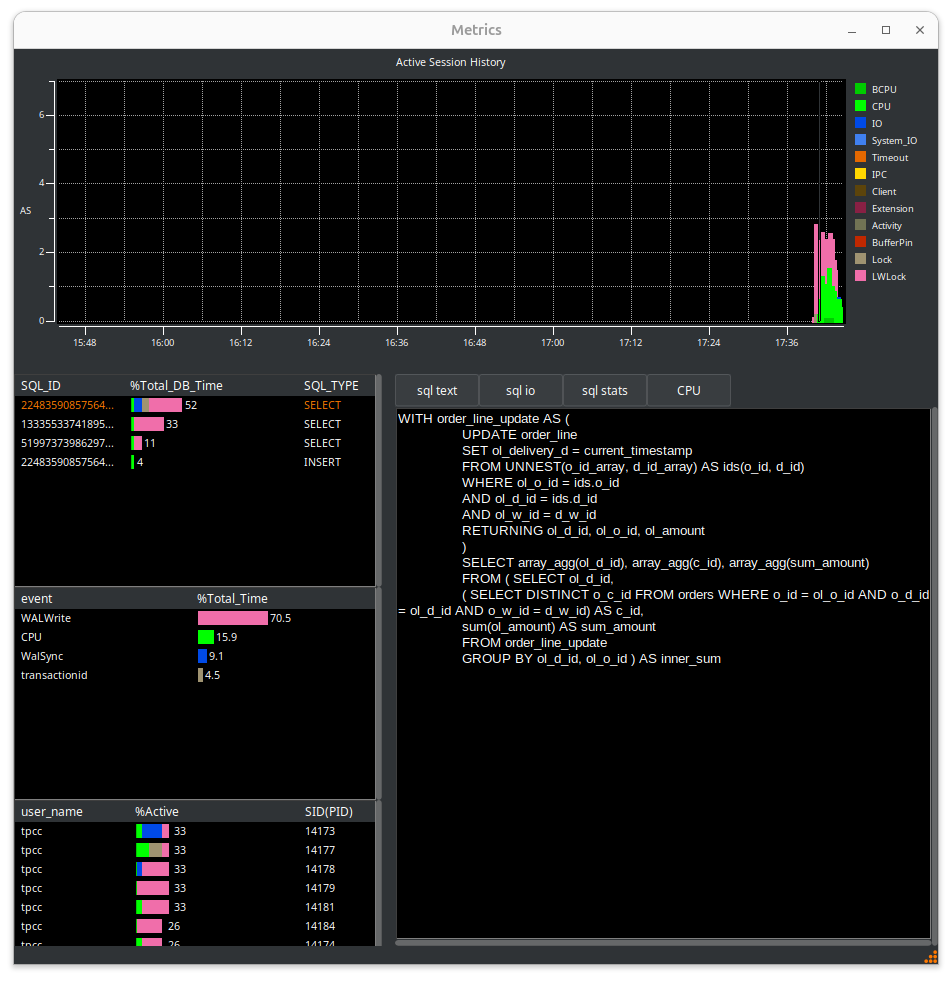

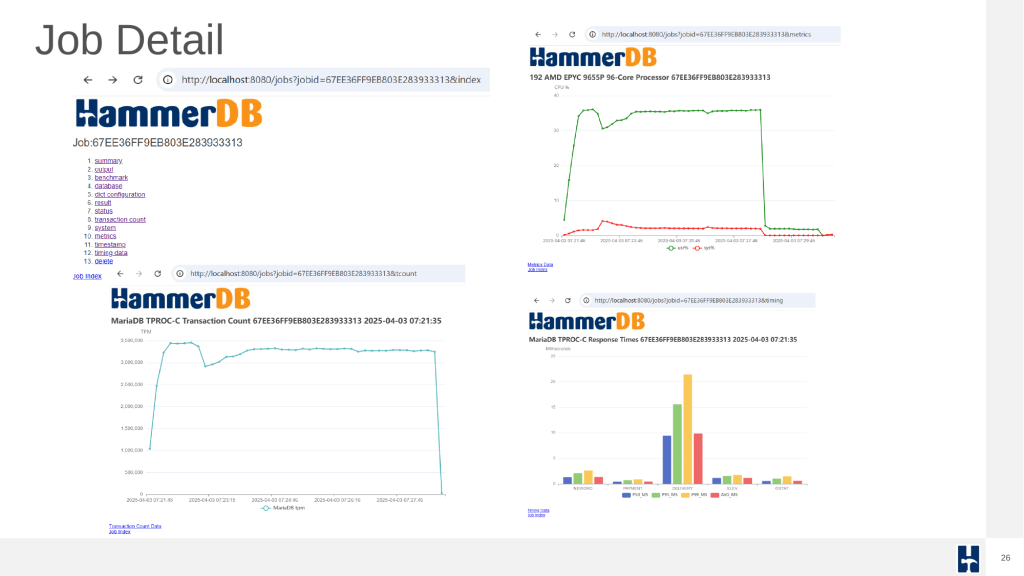

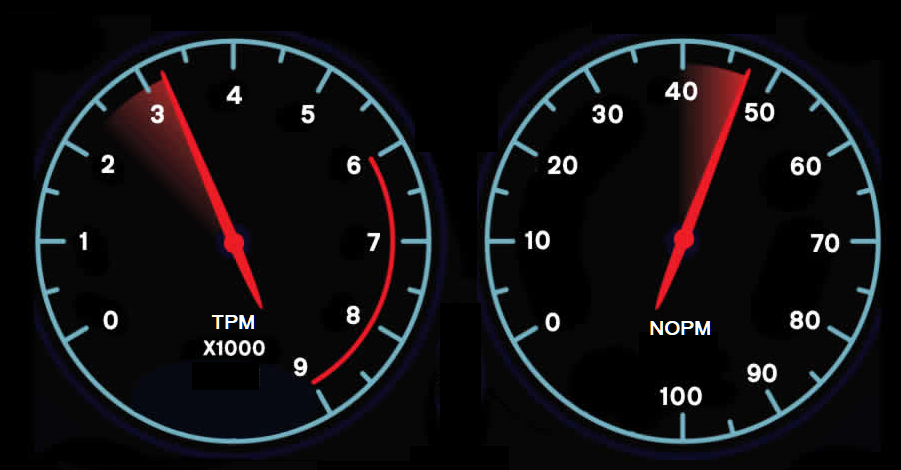

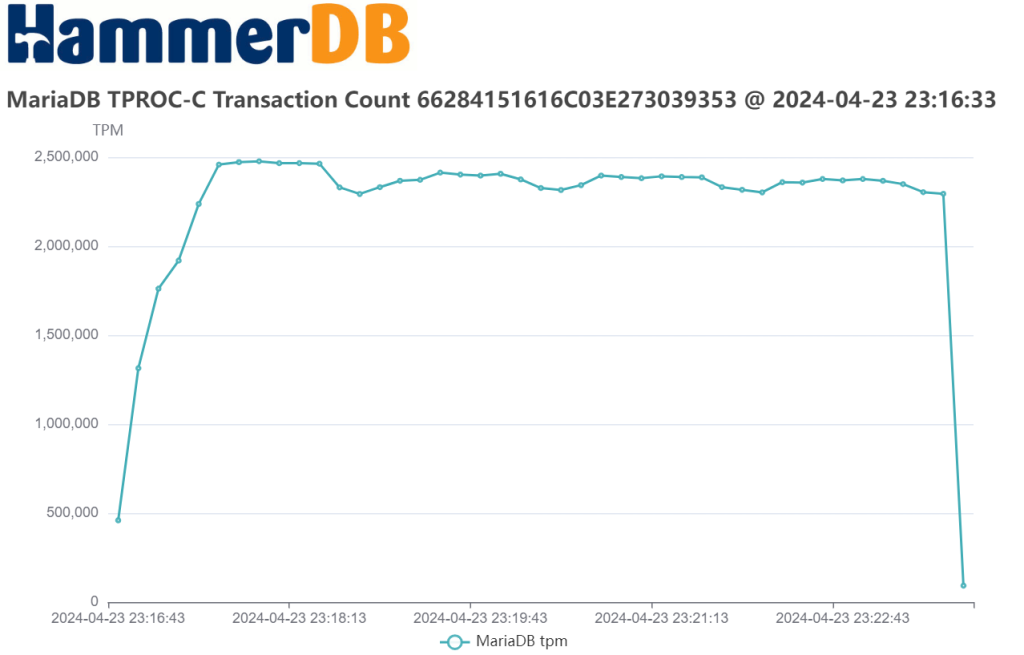

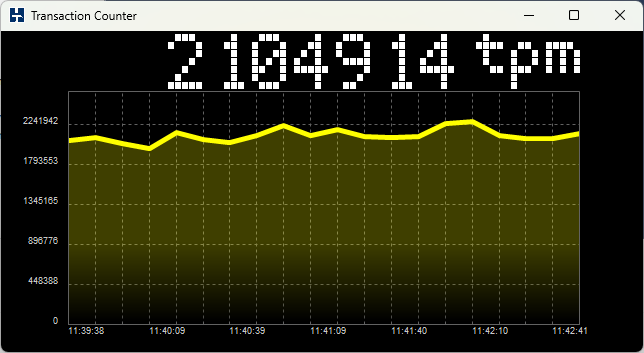

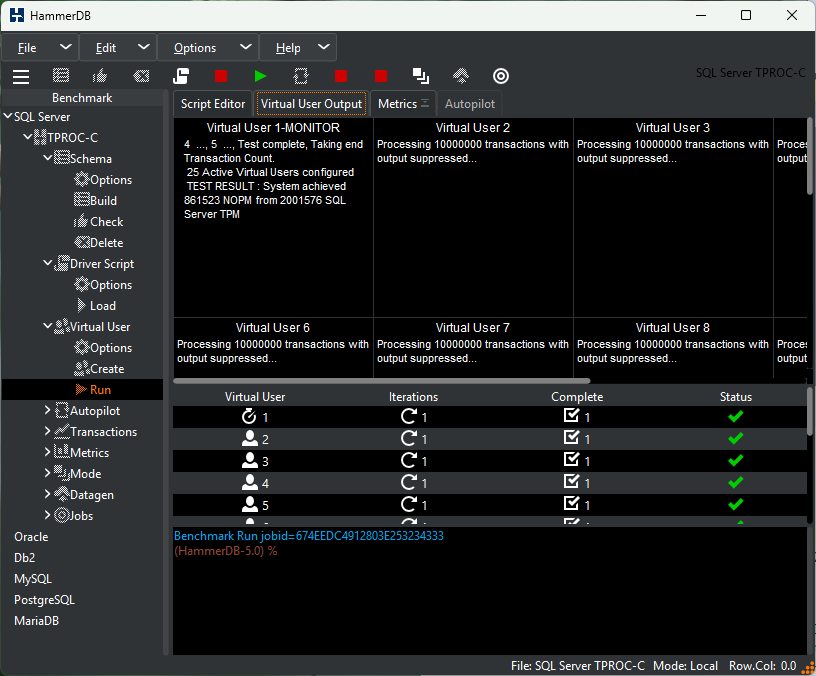

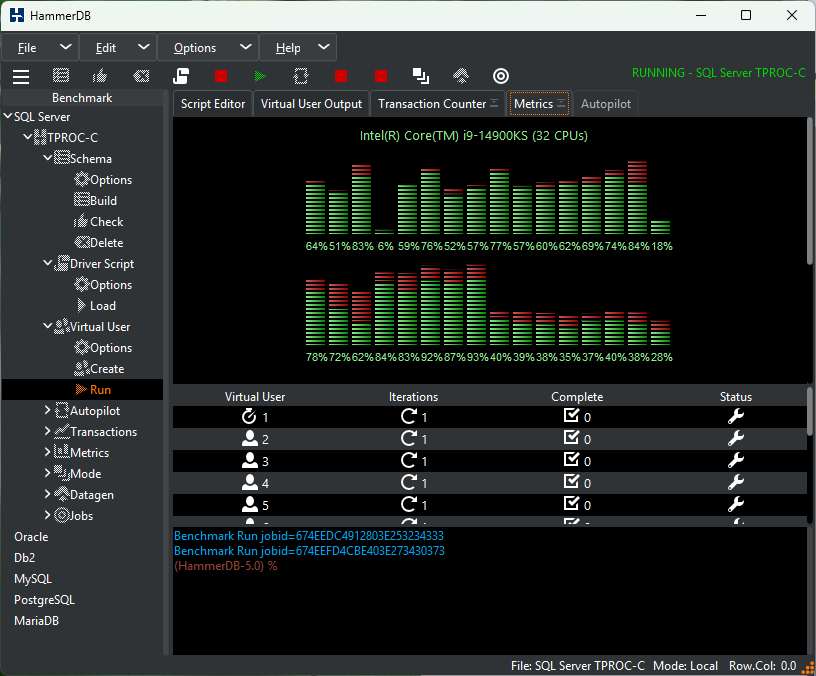

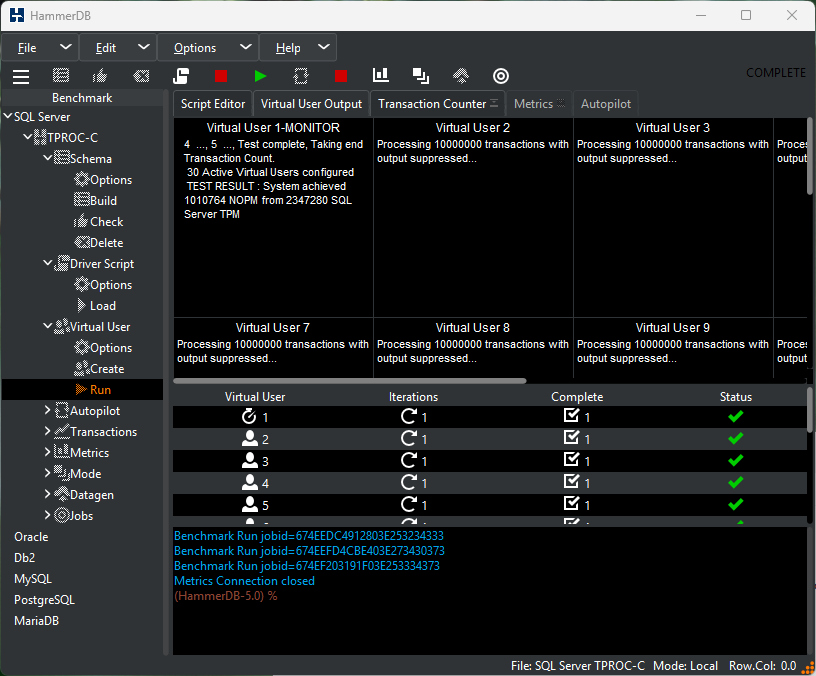

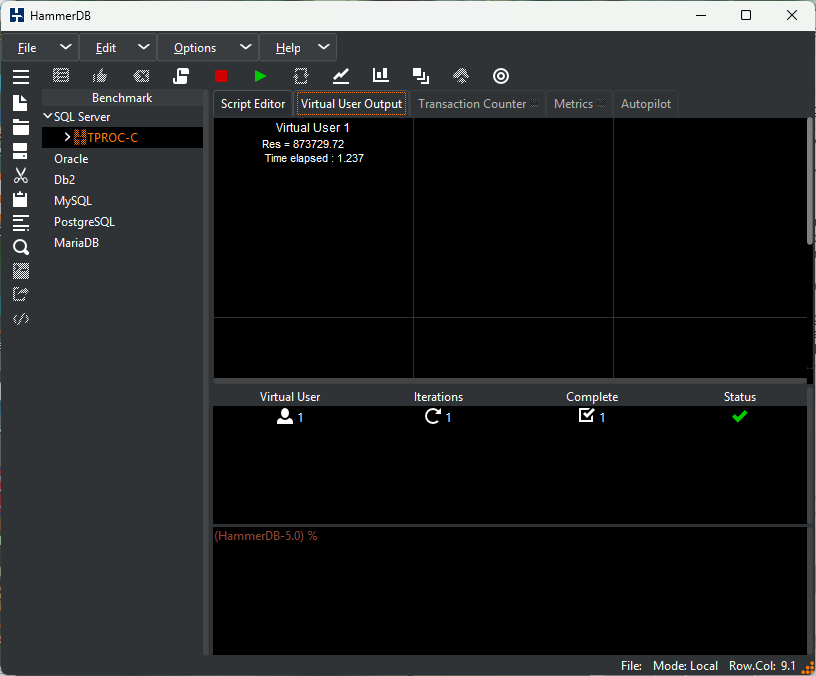

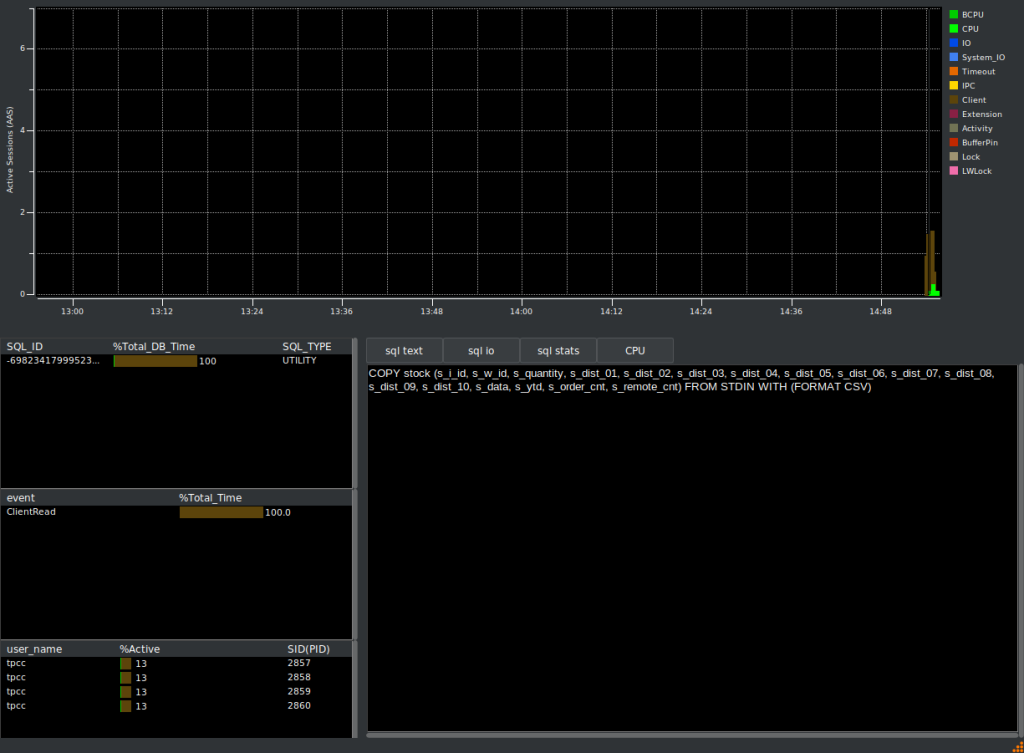

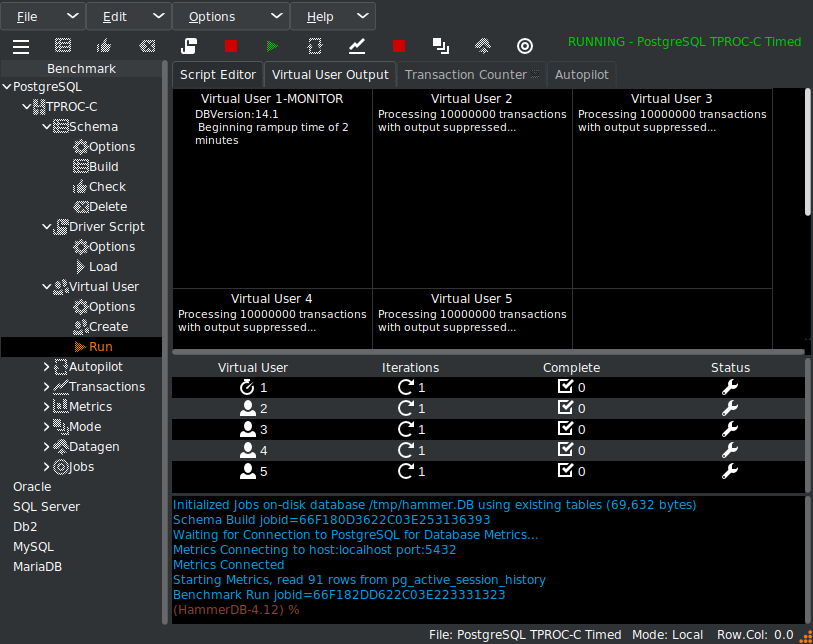

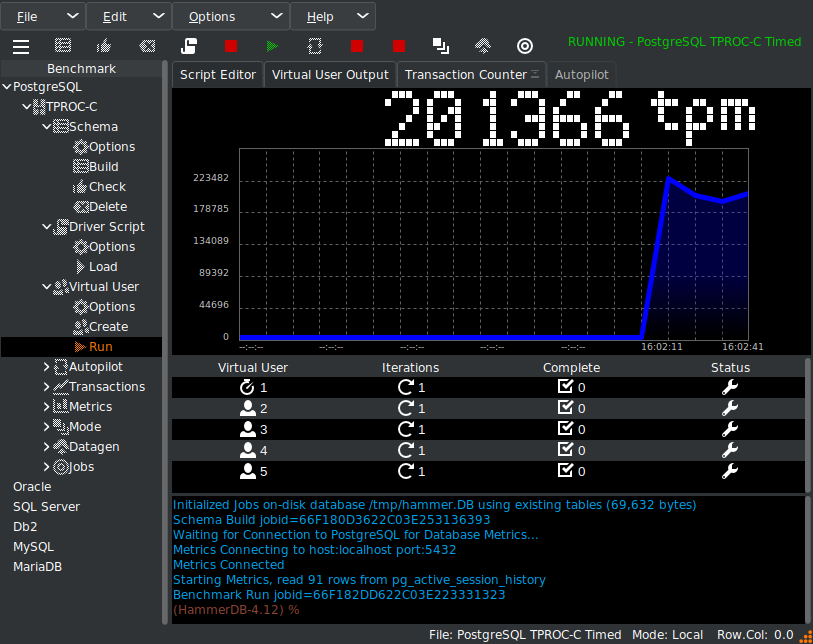

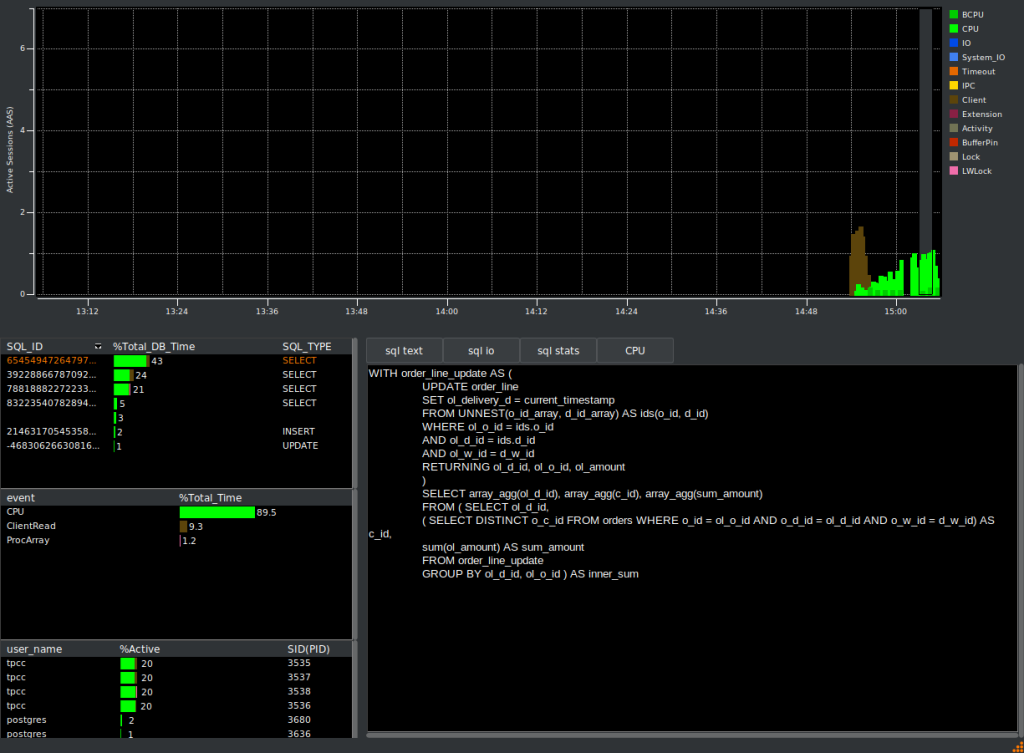

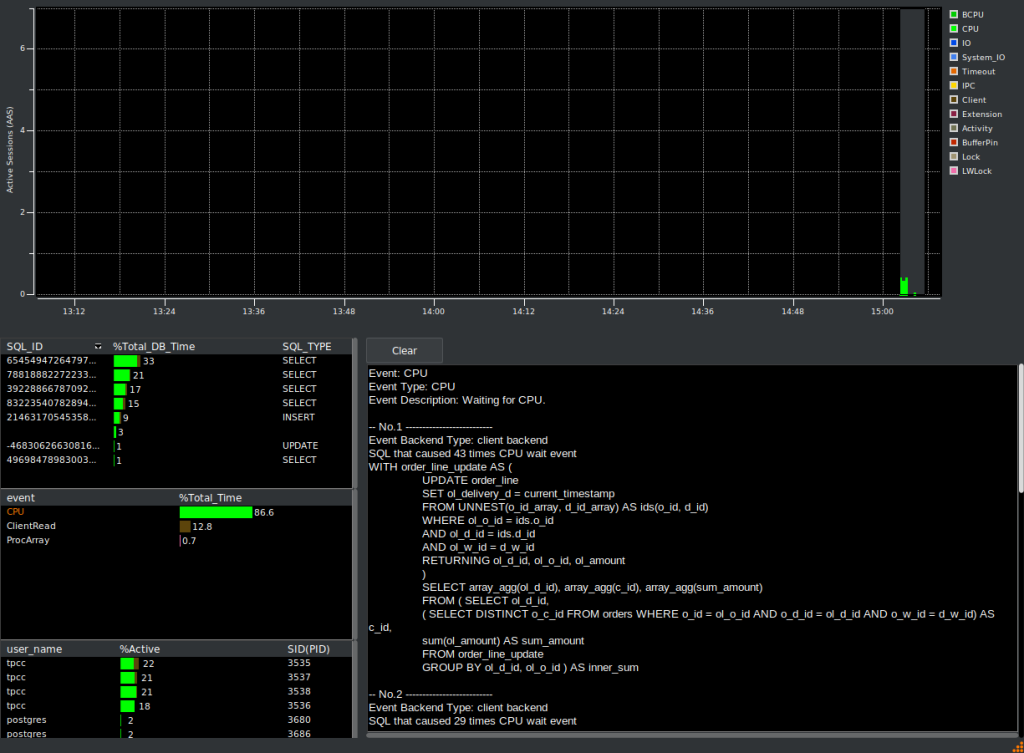

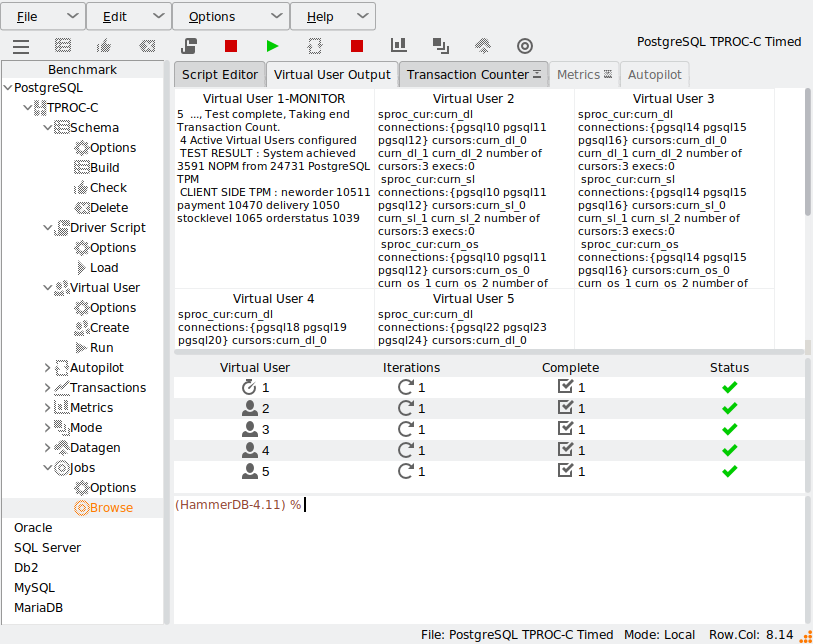

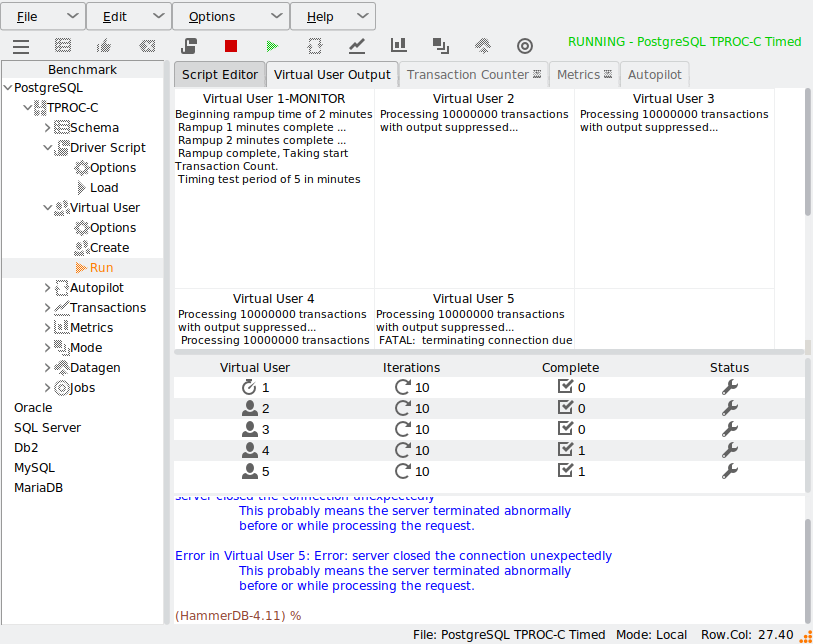

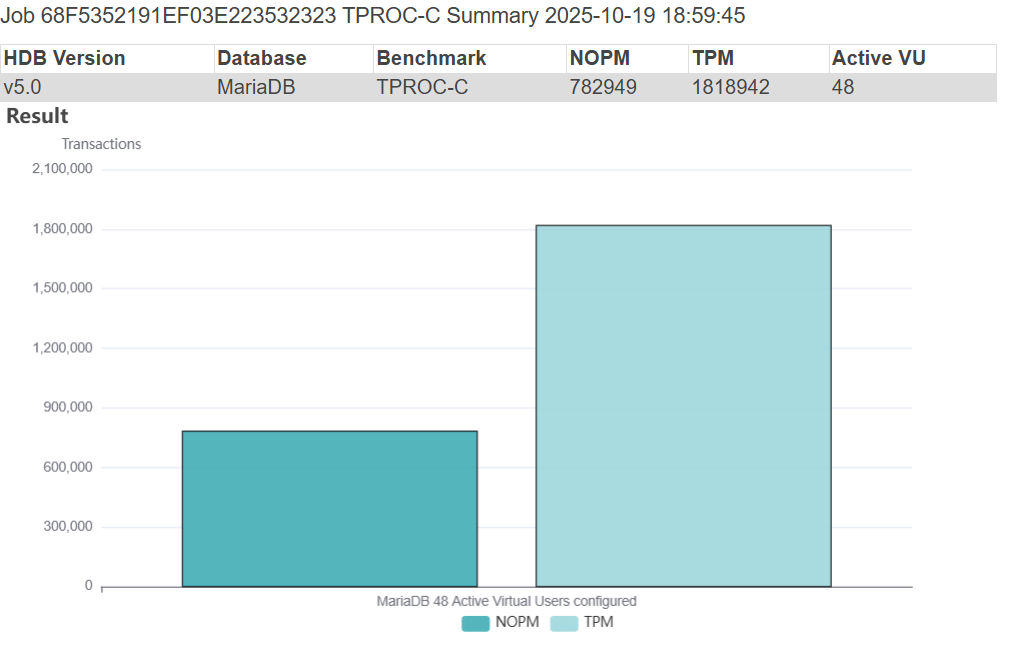

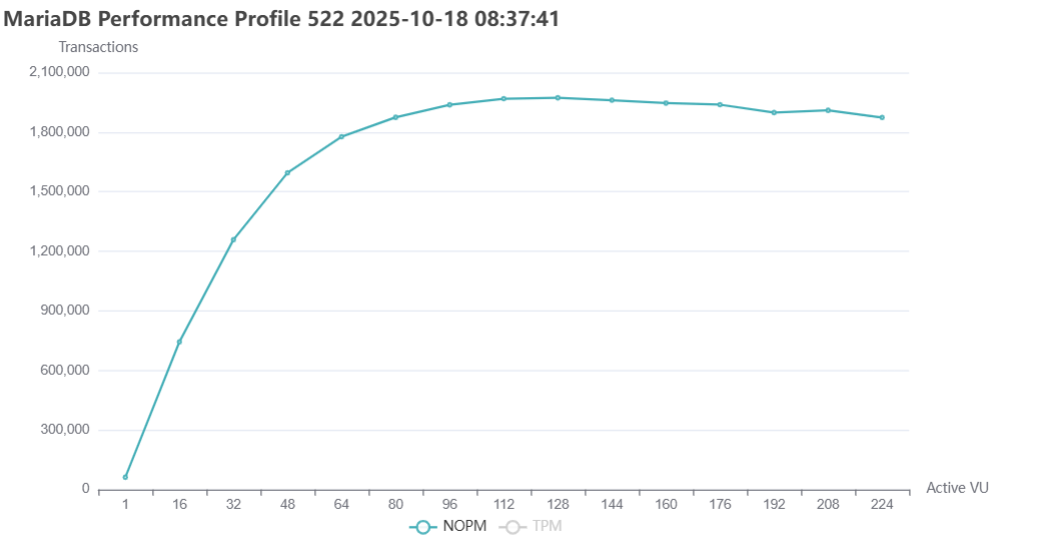

HammerDB generates graphical insight of workloads for you automatically, and the initial run of MariaDB 10.6.23-19 produced a highly respectable throughput of 782,949 NOPM which aligns with 1.8M database transactions per minute (i.e. stored procedure commits and rollbacks). As noted with topology aware scaling our peak performance was measured at 48 Active Virtual Users aligning with the CPU architecture but below the system physical core and thread count.

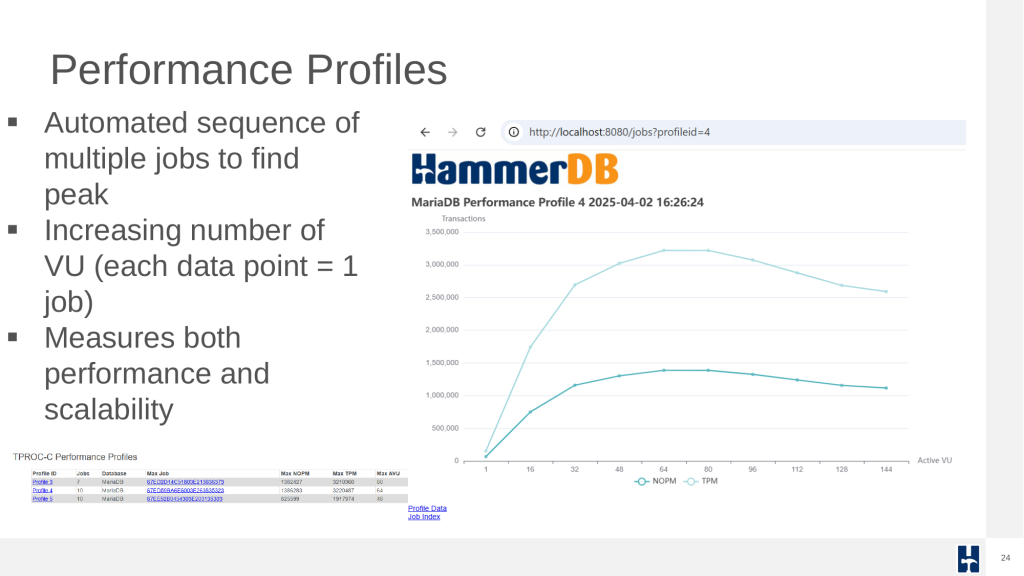

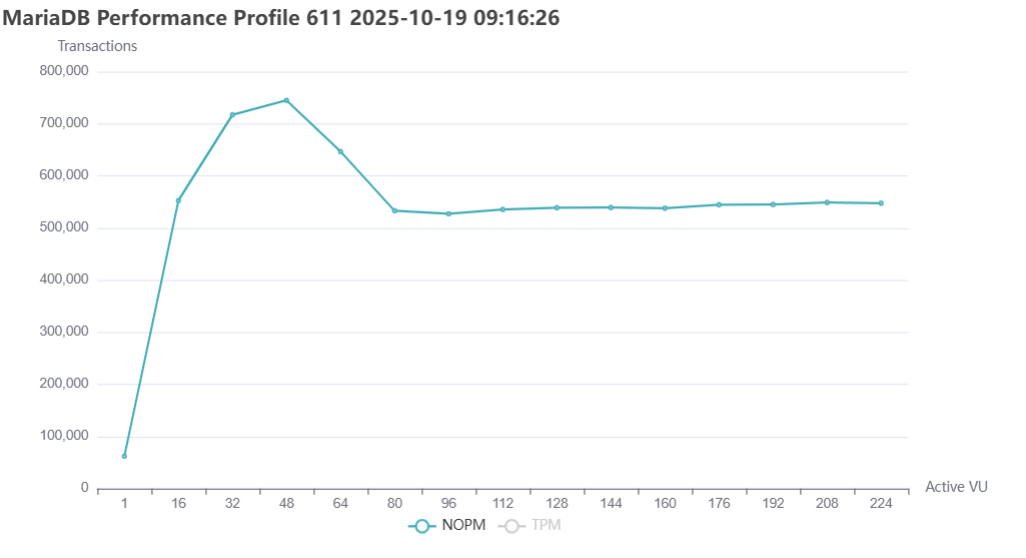

HammerDB can group related performance jobs into performance profiles. As shown in the graph this simply shows the results of repeated individual performance tests with the Virtual User count increased. It can be observed that although performance peaked at the hardware-defined 48 Virtual users it then decreased and levelled off when equalling the physical CPU count.

At high concurrency, the first clear symptom was time accumulating in native_queued_spin_lock_slowpath — a kernel sign that many threads are repeatedly contending on the same lock. Tracing that contention into the engine led directly to the transactional write path, and in particular mtr_commit, which appends redo records and advances the Log Sequence Number (LSN) on every commit.

Historically, LSN allocation and log buffer management were protected by a global lsn_lock, implemented as a futex (a fast userspace mutex). Futexes are efficient under light contention, but when many threads compete for the same lock they can become a scalability bottleneck, effectively serialising redo log throughput.

As a solution, MariaDB engineering redesigned this path to remove the global lock. Instead, threads use atomic fetch_add to reserve non-overlapping slices of the log buffer and advance the LSN. What was previously a single serialized critical section becomes a scalable atomic allocation path — a key contributor to the step-change in OLTP throughput seen in MariaDB 11.8 on modern multi-core and chiplet-based systems and you can see the implementation here.

| MDEV-21923 | LSN allocation is a bottleneck |

The nature of identifying and resolving points of serialization is that resolving one area, leads to the next and the next point of contention led to:

| MDEV-19749 | MDL scalability regression after backup locks |

Historically, FLUSH TABLES WITH READ LOCK (FTWRL)—which freezes all writes during backups—used two separate metadata lock namespaces: one for global read locks and one for commit locks. This meant normal workload traffic was split across two independent contention points. When the newer BACKUP STAGE framework was introduced, these namespaces were merged into a single BACKUP lock namespace to simplify the code. While functionally correct, this change unintentionally collapsed two queues into one, concentrating all metadata lock traffic on a single shared data structure and significantly reducing scalability under high concurrency.

MariaDB engineering addressed this by introducing MDL fast lanes, which shard lightweight metadata locks across multiple independent instances while retaining a global path for heavyweight backup locks. Under normal operation, this restores parallelism by spreading contention across multiple lock instances, while still preserving strict correctness when a backup is in progress. In effect, a global metadata serialization point was split back into multiple scalable paths, shrinking the engine’s serial fraction once again.

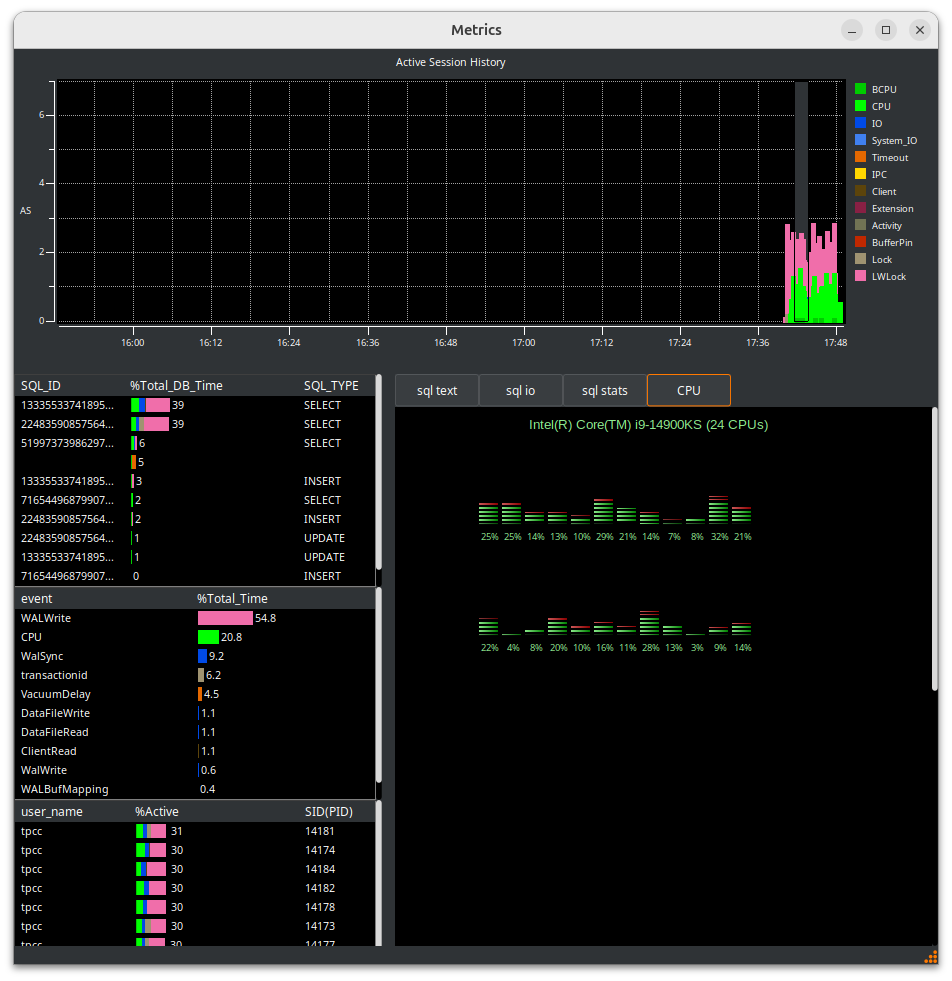

4. MariaDB 11.8.3-1 Enterprise

Although MDEV-21923 and MDEV-19749 were the key implementations to scale the MariaDB database engine across CPU architectural boundaries, additional performance related MDEVs can be viewed in the MariaDB blog post. MariaDB Enterprise Server 11.8.3-1 was the first release to include all of these changes to identify and remove single points of contention in the transactional subsystem.

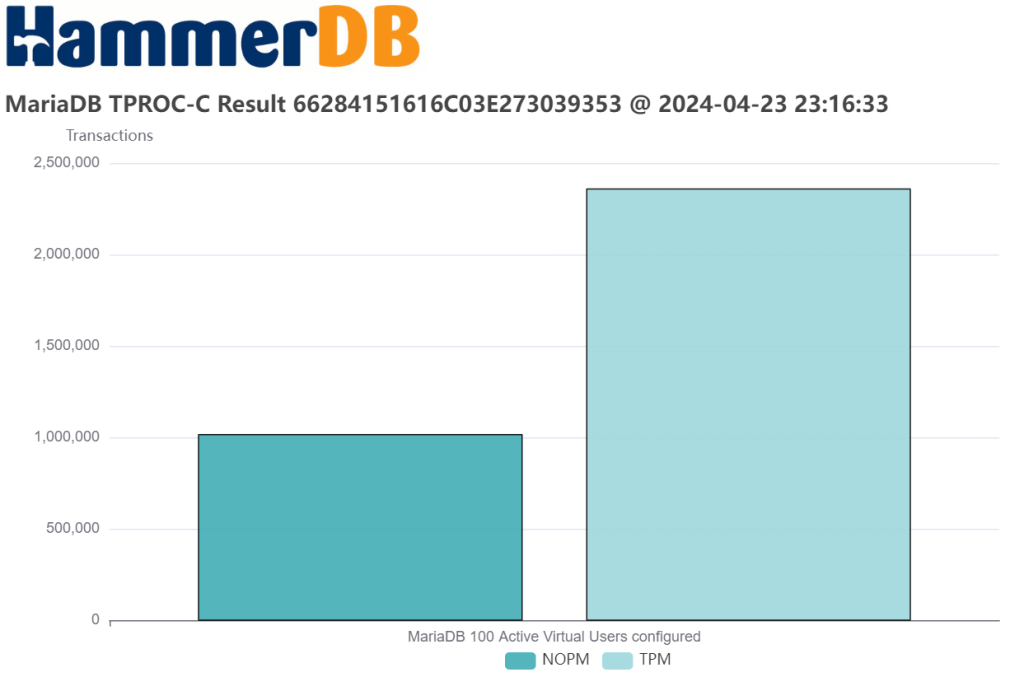

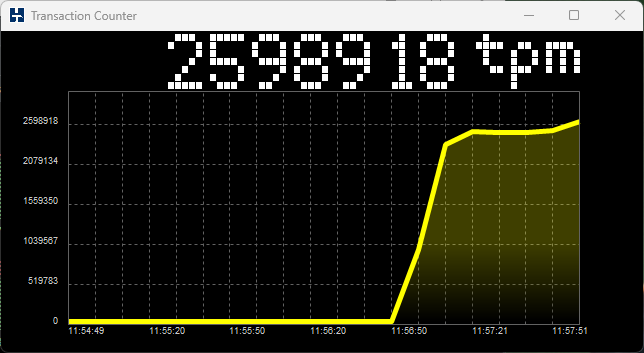

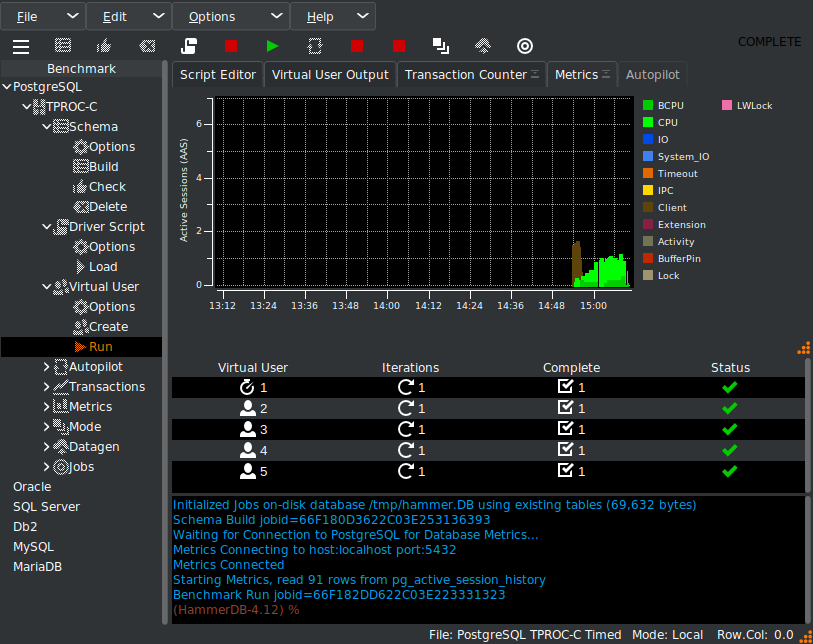

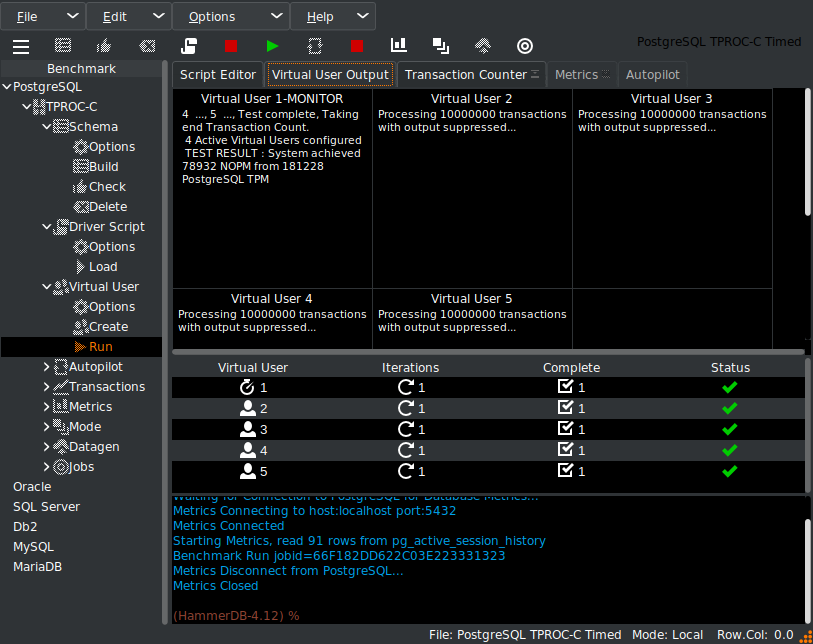

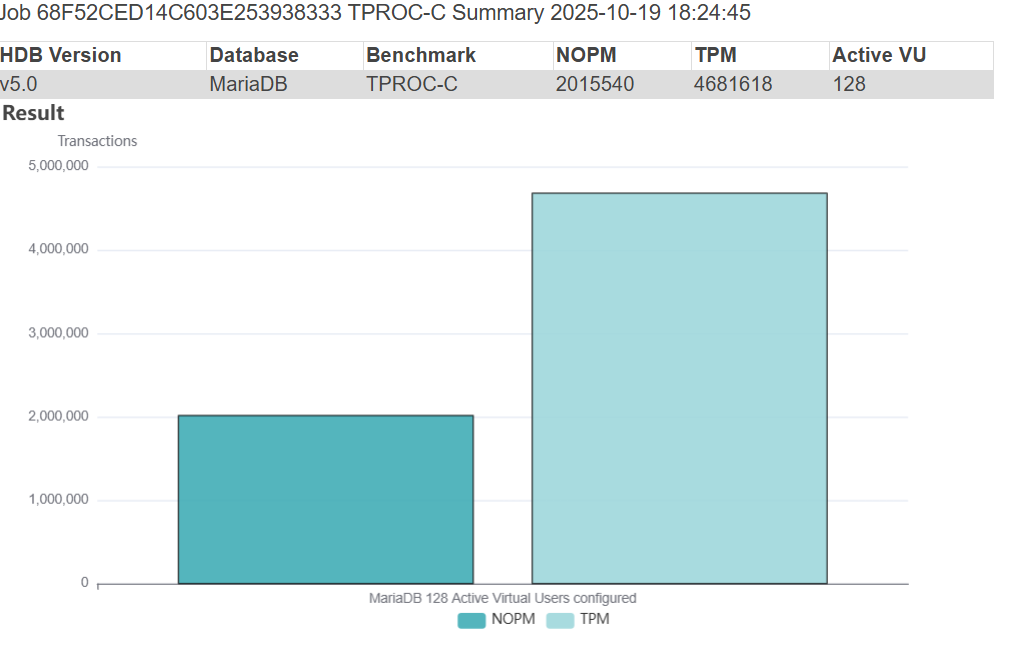

The result was 2,015,540 NOPM at 4.6M TPM for MariaDB Enterprise Server 11.8.3-1 more than 2.5X higher throughput than MariaDB 10.6.23-19 on the same server.

The resulting scalability curves closely follow extended USL predictions and align with hardware topology boundaries, indicating that core engine serialization has been substantially reduced.

5. Continuous Performance Engineering

As we have seen removing one point of serialization inevitably reveals the next. This is the nature of performance engineering at scale: each architectural fix shifts the scalability frontier.

Work is continuing to further improve concurrency and topology-aware scaling aligning MariaDB development with modern database hardware. HammerDB will continue to collaborate with MariaDB engineering to quantify these changes and provide reproducible, industry-standard benchmarks.

Conclusion

Modern database performance is shaped as much by hardware topology as by software design. Chiplet architectures have fundamentally altered scalability assumptions, and benchmarking methodologies must reflect this reality.

Failing to account for topology effects risks conflating software limitations with architectural boundaries. Database benchmarking in the chiplet era therefore requires explicit topology-aware analysis to remain a valid decision-making tool.